Man of the ‘House’

Through a sometimes rocky half-century relationship with Houston, architect Philip Johnson designed the city’s most famously restrained modern mansion and its most imposing Reagan Era skyscrapers. A new book details how an erudite New Yorker made an indelible mark deep in the heart of Texas.

Philip Johnson, the late icon of modern and postmodern architecture whose many feats include New York’s Lipstick Building, gave Houston its design pedigree. He contributed such buildings as Williams Tower and the University of Saint Thomas’ Chapel of Saint Basil. Now, in an exhaustively detailed new biography — The Man in the Glass House, whose title references Johnson’s famous home and masterwork in Connecticut — author Mark Lamster traces Johnson’s rise, and how Houston luminaries such as Gerald Hines became his most important patrons.

But decades before Hines’ elaborate skyscrapers would make him rich — and sometimes draw criticism from design purists — Johnson got a call about a residential job for one of H-Town’s most famous power couples. Per this exclusive excerpt, here’s how the architect met the Menils in the late 1940s, beginning a relationship that would change the course of Johnson’s career — and the face of Houston.

Jean and Dominique de Menil were French expatriates who had come to the United States after the war, settling in the elite Houston enclave of River Oaks. From there Jean could run the Texas wing of Schlumberger, the family oil-services business co-founded by Dominique’s father.

In search of an architect, the two were referred to Johnson by their mutual friend Mary Callery. Her advice: “If you want to spend $100,000 get Mies, but if you only want to spend $75,000 get Philip Johnson.” The Menils, who did not yet have unfettered access to the family fortune, chose Johnson.

Callery set up a meeting between Philip and Jean over cocktails at her New York studio, a converted garage enlivened by the work of her artist friends: Picasso, Léger and Matisse. The two men, similarly outgoing and charming when the moment demanded, were a perfect match, and shortly thereafter Johnson was flying off to Houston to meet Dominique, with his first Texas commission in hand.

Though Jean was a member of the French aristocracy — a baron — and Dominique an heiress to one of the century’s great fortunes, the two were unpretentious. Jean would Americanize his name, becoming John. Yet a place in the polite society of the Museum of Modern Art mattered to them, as did the possibility of raising the cultural bar in Houston. Johnson satisfied on both counts, a sophisticated New Yorker who could bring his cosmopolitan ways to Texas. Their devotion to the arts had been charged in the years before their emigration by the charismatic Catholic priest Marie-Alain Couturier, who would commission Matisse’s murals for the Chappelle du Rosaire de Vence and Le Corbusier’s landmark Chapel at Ronchamp.

Johnson’s design was, from the exterior anyway, almost as self-effacing as the tract house in which they had been living: a light-brick single-story court house in the Miesian tradition, set back judiciously behind a curving driveway. Barely a window faced the street, and one of the few that did was an addition mandated by Dominique. Instead, light came in through a central atrium and large window walls facing the rear. Its spareness was something entirely different from the other homes of River Oaks — mansions in period flavors — that in its own way testified to the glamour of its residents. A neighbor called it “ranch-house modern,” which wasn’t far off.

The commission was not without its contentions: Dominique was not inclined to the austere interior design palette — including Barcelona chairs and other Bauhaus favorites — that encompassed Johnson’s worldview. To his great displeasure, she brought in the flamboyant English couturier Charles James to pair Johnson’s architecture with the kind of drawing room flourishes and fabrics Johnson then considered apostasy but would eventually come to appreciate.

More than 20 years would pass before Johnson — who graduated from residential design to a roster of museum and university buildings, including MoMA’s Rockefeller Sculpture Garden in New York in 1953 and the “academic mall” at Houston’s University of Saint Thomas in 1959 — found acclaim with what remains Minnesota’s tallest building, IDS Center.

The success of IDS begat Johnson’s next skyscraper commission, which inaugurated a relationship that would benefit him for decades and reshape skylines across America. It came from Gerald Hines, an Indiana native with a mechanical engineering degree (from Purdue) and an adopted drawl (from Texas) who had cut his teeth developing anonymous commercial buildings but moved on to larger things. The first was Houston’s immense Galleria mall, followed by One Shell Plaza — a 50-story, tapering shaft wrapped in white travertine that projected a lavish glare in the hot Texas sun. The design was by Bruce Graham, a principal in the Chicago office of SOM, and it suggested to Hines that there was immense profit to be made if blue-chip architecture could be coupled to rigorous budgetary forecasting and cost controls. That philosophy appealed directly to Hugh Liedtke, the chief executive of Pennzoil, who in the mid-1970s approached Hines to build a “distinctive” tower for his company in Houston.

Hines’s first impulse was to return to Graham, who responded with a structure similar in character, though only half as tall, as his Sears (now Willis) Tower in Chicago. “It was a building that was very austere,” Hines said. “I was not convinced.” Neither was Liedtke. He didn’t want another upright glass “cigar box,” and he wasn’t interested in building the tallest tower in town, because it would inevitably be eclipsed. “Distinctive” was the operative goal. And Hines was already at work with another architect who could provide that elusive quality: Philip Johnson.

Their connection came through a most unlikely source, Ike Brochstein, a Jewish immigrant from Palestine who had begun his career as a teenage cabinetmaker and built a millwork firm revered in Texas and beyond. Brochstein had supplied the teak paneling for Johnson’s Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, and the two men, equally persnickety about craftsmanship, impressed each other.

It happened that Brochstein had acquired a large parcel of land in close proximity to Hines’s Galleria, and when he wished to develop it, he sought out Hines to go in on the project. Hines, concerned that Brochstein might build a competing retail center, advocated an office park. He made a short list of potential architects, among them Graham, I.M. Pei and Kevin Roche (successor to the deceased Eero Saarinen). But Brochstein remembered his work with Johnson in Fort Worth and asked that he be added to the list. When the other candidates either dropped out or were crossed off, Johnson was the last man standing.

Johnson’s first proposal for the project was a translation of his Chelsea Walk project: concrete towers set on top of a deck with parking and retail. Hines didn’t like it, not least because he’d have to build the whole thing all at once, not one building at a time — a financing issue. Johnson came back with something more acceptable: three stepped glass towers with horizontal window bands and rounded corners that could be built in phases. For their inspiration he had reached back to New York’s 1931 Starrett-Lehigh Building, a masterpiece of industrial architecture that he and architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock had included in their landmark co-curated Modern Architecture show at MoMA in 1932.

The so-called Post Oak project was still in its infancy when Hines turned to Johnson for the Pennzoil job, which now had an added complexity: a second major tenant. The Pennzoil business had actually grown out of another company, Zapata Oil, which Liedtke had founded with his younger brother and George H. W. Bush, the future president. Together Liedtke and Bush represented a new era in Texas oil; the older, wildcatting generation that lived large and lost big was being supplanted by a Brooks Brothers breed that kept their eyes on spreadsheets and their loafer-clad feet off oil derricks. Liedtke and Bush eventually split their business in two, with Liedtke re-forming under the Pennzoil banner and Bush keeping the Zapata name. It was Zapata that was to be the second tenant in Liedtke’s proposed tower.

How to put two signature tenants in a single building? Johnson’s first attempt, a cool Miesian tower modeled on his Seagram Building in New York, a 1956 collaboration with van der Rohe, was rejected — too boring. The solution, prompted by Johnson’s longtime associate John Manley, was deceptively logical: Build not one but two towers, and connect them at the base.

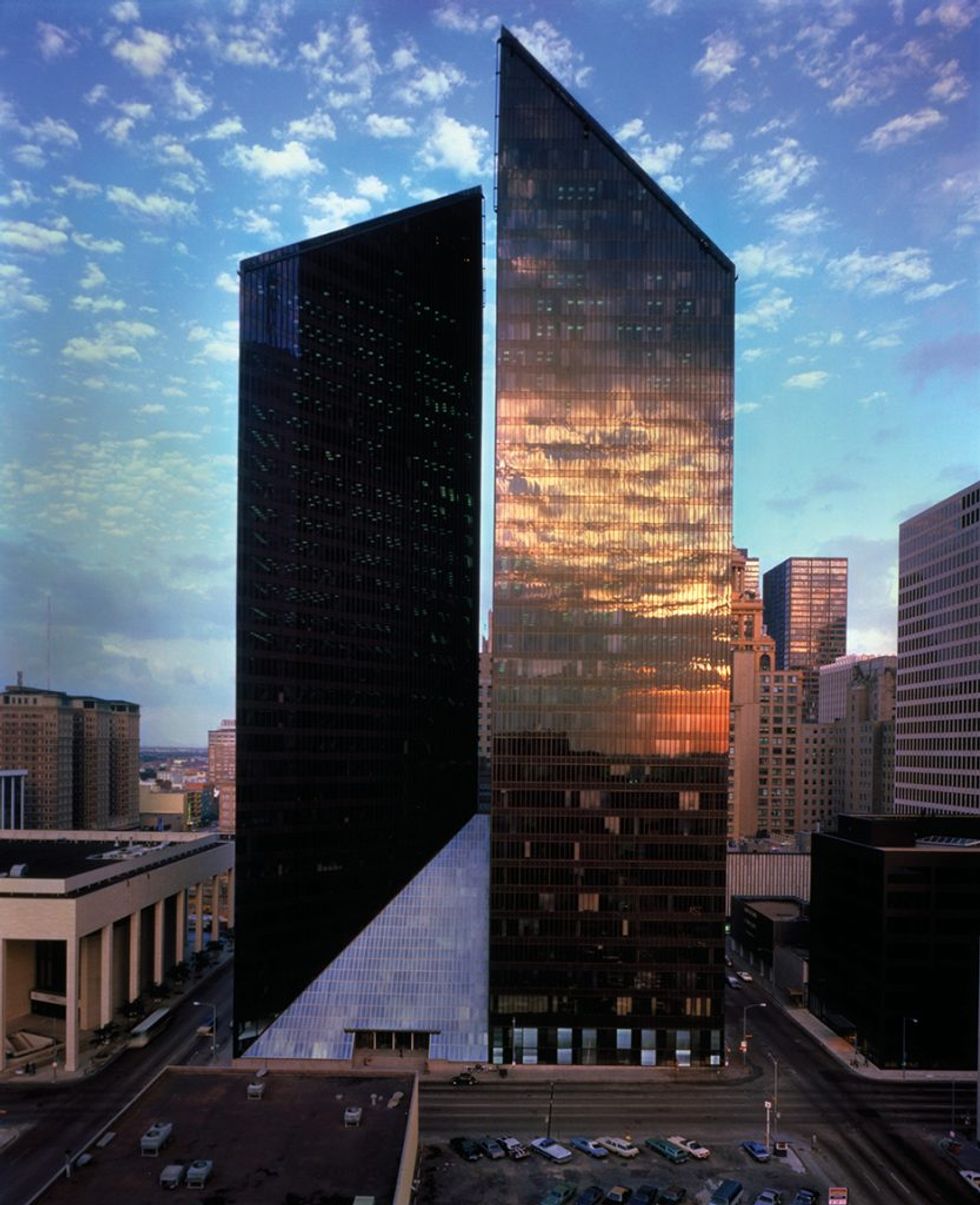

Sitting with Hines in his Seagram Building office, Johnson sketched out a diagram that looked like NBC’s pre-peacock logo, a pair of kissing trapezoids. That was how the buildings would look from above, except they would not actually kiss — there would be a slim gap between them, with a soaring glasshouse atrium bringing them together at street level. Hines approved, but when a model was shown to Liedtke he was still dissatisfied. The buildings had flat roofs — again, boring. A quick-thinking Johnson plucked one of the wedge-shaped atrium blocks from the model and stuck it atop one of the towers. “Yeah, that’s it,” said Liedtke.

Hines was also happy. Although it seemed to defy conventional wisdom, Johnson’s paired 37-story towers cost 20 percent less than the 55-floor building Graham had proposed: The shorter buildings required fewer steel columns and allowed for more parking. Using an architectural version of the “trust but verify” system, Hines had all the drawings prepared in the Johnson office completely redone in Houston, auditing them for cost efficiency. (Johnson clients who neglected to follow similar procedures tended to deeply regret it.)

Fears that the top floors, with their angled walls and diminishing floor spaces, would be hard to rent proved to be exactly wrong. Hines could actually charge a premium for those unique “prestige” spaces. Liedtke himself occupied the top floor of the Pennzoil building.

By the early 1980s, Johnson’s firm had grown tenfold, and gotten very busy. Much of that new work came from a single source, Hines. With the economic crisis of the 1970s past, the developer embarked on a spate of building across the country, much of it designed by Johnson and his young partner John Burgee. The first in this series was San Francisco’s 101 California Street Building, a granite-and-glass megastructure with a stepped circular plan — imagine the IDS Center forced through a tube — and exposed concrete columns at the base. The building was largely forgettable until it achieved an unwanted notoriety in 1993, when a deranged gunman, Gian Luigi Ferri, took an elevator to the 34th floor, donned protective headgear, and embarked on a killing spree that was then unprecedented.

It was the last Johnson tower that could be classified as “modern.” Henceforth Johnson’s skyscrapers would lean in to history with progressively more zeal, beginning with the Transco (now Williams) Tower, another production for Hines, this time on a site in Houston near the Galleria and the Post Oak development.

As with Post Oak, Johnson looked back to New York’s prewar history for inspiration, to the Beekman Tower, an Art Deco jewel he could view from the window behind his desk in the Seagram Building. The Beekman was built of warm beige brick with vertical channels and stepped setbacks at its crown; Johnson’s interpretation more than doubled it in size, from 28 to 65 stories, and sheathed it in reflective glass, though not entirely: In a bid for additional grandeur, Johnson tacked on a monumental granite entry gate at the base that was dramatically at odds with the rest of the building. Urbanistically it couldn’t have been further from the Beekman, which was set within New York’s dense street grid. With an open site in Houston, Johnson fronted his building with a linear park bordered by oaks, a composition that culminated at a large hemispherical fountain set behind Palladian arches. In case anyone failed to notice this new addition to the scene — and with its priapic vertical form it was intentionally hard to miss — Johnson installed a rotating searchlight at its top, marking its place in the sprawling Houston landscape.

If Transco took the forms of history and dressed them in modern materials, Johnson’s Republic Bank (now Bank of America) Center looked back to history — specifically, to the Dutch Gothic of the seventeenth century — but without the modern drapery. The composition, developed by Hines, sat on a full city block across the street from Pennzoil Place, and initially Johnson thought to match it with a complementary design. Hines rejected that proposal in the interest of contrast. There were other demands, among them that it not block Pennzoil chairman Liedtke’s skyline view.

At 780 feet it towered over its neighbor, but Johnson solved the view-corridor problem by giving the building three pointed gables that stepped back as it rose, so that by the top it was far reduced in bulk. Instead of glass, its facades were of red Swedish granite, giving it the impression of an immense, scaleless mass at ground level. Marked on the skyline by its stepped roof, at the street it was defined by an enormous banking hall — actually a separate but attached building. This was an essay in architectural decadence, an immense box with 167-foot-high ceilings, as well as arches, columns and arcades in marble and ebony.

It looked rich, and that was the look of the moment in the burgeoning Reagan era. It was morning in America, and Johnson’s solid buildings, with their familiar architectural elements — columns, pediments, vaults, gables, and so many other details jettisoned as extraneous by modernists — spoke to a conservative clientele open to a corporate language that corresponded to the white-picket-fence suburbs to which they returned after work.

Soon Johnson/Burgee had towers going up across the U.S. There were towers everywhere, a string of similarly forgettable buildings, unless one happened to live or work in one of those cities, in which case their pharaonic scale and retrograde presence made them unavoidable touchstones. Each one had some distinguishing characteristic: Atlanta had pergolas. Dallas got barrel vaults. Denver got Palladian windows that looked like wallpaper. Louisville’s was capped by a hemispherical dome. Chicago and Detroit got gables at the skyline, San Francisco a mansard roof with kitschy sculptures.

They had one thing in common: They were all profitable. Johnson’s operation, a little firm that once struggled to land residential work in the Connecticut hinterland, was now pulling in nearly $20 million annually in billings, with seven-figure salaries for the partners. For the first time, Johnson could claim to be rich of his own accord.